If I were to ask where the Maya lived, most would answer: southern Mexico. Is this correct? Yes. Was this the only place where they lived? No.

When I began my research into the Huastec I thought that they looked like a very interesting offshoot of the mainland Maya, however as my research continued past their ruins and statues, I found the story of an under-acknowledged people. A people who have faced persecution throughout a large part of their history, and who feel it still today. To make matters worse, Mexico – a country that prides itself on its indigenous heritage – often ignores this group in conversations celebrating their indigenous roots. Scholars rarely excavate or study this culture, with many of the last major excavations being undertaken in the mid 20th century. This article is aimed at bringing awareness to a cultural group who has been swept under the rug of history.

What Makes the Huastec Different?

While every group of people is unique in their own way, the Huastec stand out in pre-conquest Mesoamerica because they appear to be the northernmost Maya group. While the rest of the Maya people were living in the jungles of the Yucatan peninsula, the Huastec emigrated north along the Mexican gulf coast, settling in modern day Veracruz. They would have been surrounded by foreign groups on all sides who spoke different languages, worshiped different gods, and practiced different cultural traditions.

As far as we know, the Huastec did not have a developed writing system, therefore we don’t have any first hand written accounts by them. They appear to have separated from the mainland Maya before the advent of the Mayan glyph system. The name Huastec is not even what they called themselves. It is a Nahua word (Aztecan) referring to the region where these people lived (Richter, 2010). The cultural group we call Huastec actually call themselves the Teenek. They still exist today. For this reason, I will respect the community’s culture, and refer to them as the Teenek for the rest of this article.

To make matters worse, many of the writings we have from the Spanish regarding the Teenek, come from the Aztecs (Richter, 2010). This is problematic in multiple ways. Of course, the Spanish were biased, and we can only trust their descriptions through the lens of knowing they were colonists and the Aztecs were not friends of the Teenek, either. The only accounts we have from the Aztec show a disdainful relationship, where the Teenek were viewed as savage and lesser people due to cultural differences. We’ll still go over these accounts, keeping in mind that even though the Aztecs and the Teenek were both conquered by the Spanish, they were not necessarily on the same side. The Aztec accounts need to be taken with a grain of salt just as much as the Spaniards’.

The cultural group we call Huastec actually call themselves the Teenek.

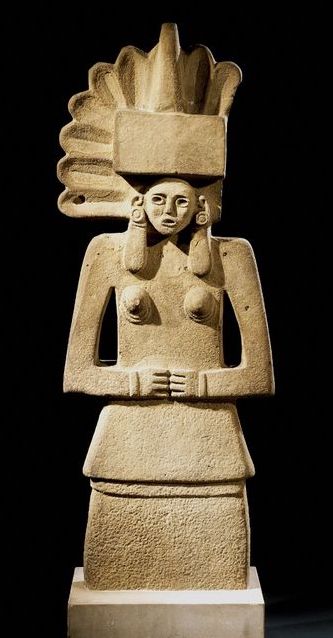

Much like the political situation for the Maya in the Yucatan, the Teenek were not a unified empire. Instead, they lived in distinct city-states, sharing cultural traits with one another, but not having an overarching leader. There were commoners and nobles, priests, local lords, and perhaps slaves as well. Sculptures from Teenek sites show women as warriors and queens, most often combining these two motifs. Not only do these sculptures imply the rule of queens, but there is also ethnographic evidence that women sometimes took on the role of queen in Teenek communities. It’s not yet known how common this was, however it definitely was happening.

For how little literature there is, there’s a plethora of theories surrounding the origin of these people and who they were influenced by. Some researchers believe that following their arrival in the region, they appear to have been isolated and uninfluenced by their neighboring cultures until the Postclassic period. Other researchers think that they could have been in contact with the Veracruz, Totonac, and Toltec people – or any combination of the three. For the sake of this article, I would like to focus on the Postclassic period where there is better studied, and more consensus. Our knowledge of the early Teenek culture may be subject to change, as more research is needed.

Politics

As I mentioned, we will jump to the Postclassic period beginning at around 950 A.D. and ending with colonization by the Spanish. Like elsewhere in Mesoamerica, the Teenek eventually grew to have large settlements that we would consider cities. The Aztecs took note of these growing settlements and proceeded to subjugate the provinces of Oxtlipa and Tamuin which were both culturally Teenek (Stresser-Péan & Stresser-Péan, 2001). With the rule by these new outsiders, Teenek artwork began to resemble other Mesoamerican cultures. Some scholars refer to this as the Postclassic international style, which we will discuss more later. The important takeaway is that after the Aztec conquest, the Teenek were brought into the greater shared Mesoamerican culture.

Despite the Aztec encroachment, the Huastec region had not been entirely conquered and much of the coastal land remained independent. In conquered land, the Aztec soldiers who remained, established family lines there. This started a dynamic where the noble class shifted to Aztec and the commoners still retained their Teenek culture. Spanish priests recorded this happening in Tamuin, where the aristocrats all spoke Nahuatl (Aztec language) and the rest of the populace spoke their Maya language (Stresser-Péan & Stresser-Péan, 2001).

Under Aztec rule the Teenek had to pay taxes to the empire. For them, this came in the form of cotton. The Teenek were masterful cotton farmers and textile producers. One of their noteworthy pieces is the mantles they made. This is a loose-fitting piece of cloth that resembles a cloak (the ancient Greeks wore these as well, to give you a mental picture). It’s easy to see why they would prefer something light like this, as the region they lived in was hot and dry through most of the year. Unfortunately, even with this tribute, the Aztecs did not particularly enjoy their dealings with the Teenek. One of their issues was the Teenek stance on male dress code – or lack thereof. Teenek men often walked around without loincloths which bothered the Aztec who always had their men dress modestly. Another problem the Aztecs found with the Teenek was their consumption of pulque. This is an alcoholic drink that is made using sap from agave plants. To the Aztecs, drinking this was a ritual act that had strict rules one should follow. A famous story they tell is that of a Teenek lord who attended one of these ritual events. This lord drank five cups of pulque instead of the standard four, and upon drinking the fifth he was so inebriated that he took off his loincloth to the dismay of the Aztecs. This event inspired the Nahuatl phrase used in reference to drunks, “He is the image of a Huaxteca. He drank not only the four wine jars, he finished the fifth.” In addition to this, the Aztecs saw the Teenek as too indulgent in musical entertainment, and users of dark magic (Diehl, 2000). It is important to remember that the Aztecs are the conquerors of the Teenek, and already viewed them with disdain. Myths like this are fanciful and it will always be impossible to decipher what is true and what is fiction. Still, I decided to add it because it shows the relationship that these groups had.

“The first town we came unto is called Tancuylabo, in which there dwell many Indians, high of stature, having painted their bodies with blue, and wear their hair long down to their knees, tied as women use to do with their hair-laces. When they go out of their doors, they carry with them their bows and arrows, being very great archers, going for the most part naked. In those countries they take neither gold nor silver for exchange of anything, but only salt, which they greatly esteem….” – John Chilton, English explorer, 1572 (Stresser-Péan & Stresser-Péan, 2001)

The Teenek people expressed themselves in many ways. They were known for dyeing their hair and bodies red and yellow, parting their hair down the middle and letting it fall over their ears. They filed their teeth, and threaded feathers, or palm leaves through their nose. They wore mantles made of cotton and capes made of feathers. They had jade and leather arm bands. Women wore skirts and wove colored cloth strips through their hair, as well as feathers (Diehl, 2000). And as previously mentioned, the men preferred not wearing loincloths. As you can see, these people dressed grandly and with no less style than anywhere else in mesoamerica.

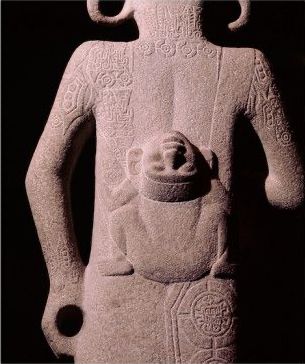

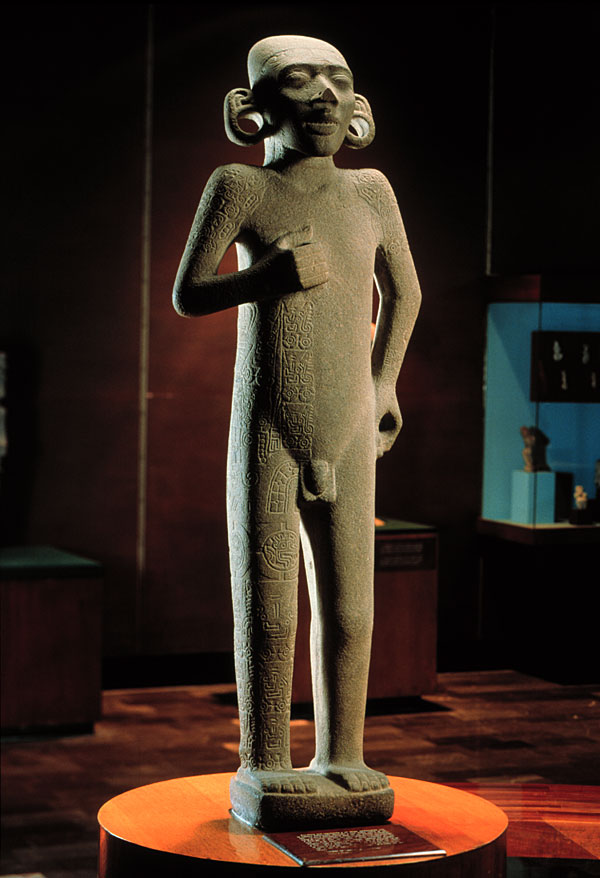

As for artistic expression, I find the sculptures they made some of the most interesting and captivating in all of mesoamerica. Not only are the stylistic elements unique to the region, the things depicted are as well. The Teneek had a near 50/50 split of male and females depicted in their sculptures. Nowhere else in mesoamerica was it so balanced. Another interesting thing of note is the depictions we have of males carrying infants. El Adolescente is a famous sculpture showing this, as an infant is held in a sling on the back of a man (Wyllie, 2015). This is not an isolated case either, as we have many representations of this. Combined with the depictions of female queens, there were very interesting gender roles at play in the Teenek culture.

One of the main deities represented in Teenek sites is Tlazolteotl. This is a female goddess who rules over the domains of sex, filth, fertility, sin, and disease. I know that may not sound like an appealing god to worship, but you have to put these cultures into perspective. In a polytheistic world, you wouldn’t likely worship only that god, but try to appease it when needed. Say you were trying for a baby, you might make an offering to her so that you conceive. The goddess likely was not worshiped in the same way we view god in a monotheistic system. Anyway, another name for her was Ixcuina which means “lady of the cotton.” This, combined with the amount of statues we have from Teenek sites depicting her, makes researchers believe that she originated in the Huastec region. As time progressed she would have been adopted into the greater mesoamerican pantheon and worshipped in cultures like the Aztec. While she was often known for lust and adulterous acts, one of her more noble properties was her ability to absolve sin in those who confessed to her. Overall, the Teenek likely worshiped her for her fertility properties (Taube, 2015).

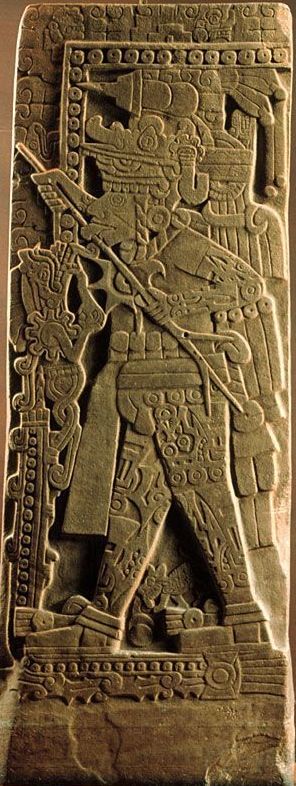

The other most prominent deity to the Teenek was a hybridized god. In other mesoamerican cultures these gods are depicted as separate entities, but in Teneek statues, they are blended into one person – or one creature. What I’m referring to is Quetzalcoatl and Ehecuatl. Quetzalcoatl is a common mesoamerican god. He is a giant feathered serpent that has symbolized many different things to his worshippers. Commonly he is seen as a creator god, a harbinger of wisdom, and war. Ehecuatl is often depicted as a humanoid man with a mouth that looks similar to a beak (Taube, 2015). He is known for being the god over the domain of wind and air. The Teenek seemed to be one of the cultures who synthesized these two deities. Quetzalcoatl was the central figure in a cult that spread all across mesoamerica at the time, now referred to as the Feathered Serpent cult network. Note that the use of the word “cult” just means that it was a popular religious idea at the time, not that its followers had to worship in secret or anything like that. Depictions of this god are common in Teenek sites. They likely associated him with battle, and we see depictions of both male and female warriors in relation to it. Sculptures of nobles and elites show them wearing regalia that is meant to symbolize this god, such as large headdresses which would have been made of macaw feathers (Taube, 2015). These headdresses were used by the elite all throughout mesoamerica as a status identifier, and here it would be no different. It is an easy way to show that you are part of the high status group and are a member of this Feathered Serpent cult.

Tamtoc is perhaps the most significant site that we have for the precolumbian Teenek culture. Much of this significance comes from it just being the most extensively studied Teneek site. It has plazas and mounds, residential areas and altars. One fascinating thing about it is the layout of buildings. The earliest built buildings all have a distinct circular or horseshoe shape which is unlike all of the cultures around it. Perhaps this could be a glimpse of the early Mayan settlers in the region, bringing with them a foreign style. With recent research, some archaeologists speculate that the settlers of Tamtoc may have migrated from the region of Chiapas in southern Mexico (Alarcon & Ahuja, 2015). This is theorized due to their similarities in ceramic production, and a similar calendrical system, which we speculate to have found on a sculpture discussed below. I do want to point out that the circular architectural style is not common in Chiapas. The style may have been an independent creation, unique to Tamtoc. As time progressed, the people of Tamtoc must have been influenced by their neighbors because we see the architecture change to the more familiar rectangular shapes that we see throughout mesoamerica. As we talk about architecture, I should mention that not much is left. These distinctive styles are only hinted at from the platforms that remain. Short platforms of raised earth are held together with stone walls – something akin to a foundation. Whatever structure was on top must have been made out of organic materials and rotted away through history.

Images:

Above right: Tlazolteotl.

Above left: Xochipilli, god of art and games.

Despite us losing some of the architecture to time, we still have a masterfully built water reservoir on the site (seen below). As water fills up in the reservoir, it drains down a canal into a freshwater lake. This system provided the residents of Tamtoc with both drinking water as well as a food source from fish. I bring this up, because it seems the residents ascribed a great importance to it. A massive sculpture unceremoniously named Monument 32, was found in conjunction with this aquatic feature. This sculpture depicts three women; two of which are decapitated, while the middle figure wears a skull mask. Streams of blood radiate from the necks of the two flanking women in shapes of “X” with an extra line through the middle connecting all the figures. The monument also has glyphs surrounding the figures, which researchers have interpreted as plants growing. The overarching theme that archaeologists believe this monument represents, is the life cycle. Agriculture and plants are fed water (or blood) and grow to feed humans and other animals. The skull figure also wears a symbol which could be a glyph symbolizing its calendrical name – perhaps relating to the growing season (Alarcon & Ahuja, 2015).

Hidden underneath a paved layer of the reservoir, archaeologists found another sculpture: The Priestess of Tamtoc (seen below). This is a naturalistic figure of a woman’s body, embedded with circular marks on the breasts and thighs. We are not sure of the meaning behind these details, but the number of dots seems to be in relation with the mesoamerican calendrical cycle of 52 years (Alarcon & Ahuja, 2015). Agricultural production was related to this cycle, and the context of the sculpture gives further proof of this likely connection. The statue was found ritualy destroyed and placed under the reservoir likely as an offering to the agriculture which the reservoir would sustain. Found with this sculpture are the ceramics which are stylistically similar to that of southern Mexico in the Chiapas region. That far south would have been under the Maya cultural sphere, and is a possible origin area of the Teenek.

Finally I would like to touch upon the cemetery at Tamtoc (on the left). In the vast majority of tombs, only women were interred there. That is not saying Tamtoc was a society made up of only women, but there appears to have been a special significance to this – perhaps a reverence, or a higher social status. Tombs held up to three individuals, which were all placed in a seated position. The middle of the small circular tombs held an upright slab of stone, and the individuals would have been placed there at different times (Alarcon & Ahuja, 2015). This makes me think they were families being placed together. The archaeology is inconclusive at the moment.

Colonization and Today

Unfortunately, the Teenek were not spared from the brutality that is colonialism. For a while they were ignored by the Spanish, as the northern region was not rich with gold or other easily exploitable resources, making it unimportant in their eyes. The excerpt from the English explorer earlier in the article was actually written a half century after colonization efforts had started, and the natives were still dressing as they always had, and living relatively unchanged lifestyles.

This ended when the Spanish realized that the exploitable resource was people. Thousands of Teenek were captured and sold as slaves to islands in the Antilles. The slave trade lasted for five years, until it was finally stopped. This was too little too late however, as the population was drastically reduced, and those who had been taken had little chance to ever see their homes again.

The Teenek would then be impacted by war. The Chichimeca War was between a nomadic confederation of tribes, and the Spanish. The Teenek, who were caught in the crossfire, saw many of their villages destroyed. They would have to move to new towns created by the Spanish which were meant to group the natives together for better control. Although insidious by design, the Teenek were relatively safe here, as the Spanish protected against raids by Chichimeca groups. This soon changed however, when the Spanish realized that the land was not going to be profitable. They sold chunks of land off to rich Spaniards and creoles (Stresser-Péan & Stresser-Péan, 2001).

As time has worn on, the Teenek have been relegated to workers on plots of land which are no longer their own. The region where they had once farmed maize now is filled with cattle ranches owned by foreigners. The Teenek have only maintained a foothold of property ownership in the town of Tantoyuca, where small hamlets exist in the surrounding hills above the city. Families are forced to live together in one room bamboo huts where they lack necessities such as running water or electricity. Today, the Teenek are one of the most impoverished groups in Mexico (de Vidas, 2002). Through maintaining their survival whilst being exploited for labor, many modern Teenek have lost connections to their indigenous past. These people deserve to have their voices heard and they deserve to be helped. They do not deserve to be a forgotten footnote in the history of mesoamerica.

References

Alarcon, G., & Ahuja, G. (2015). The Materials of Tamtoc: A Preliminary Evaluation. In K. A. Faust & K. N. Richter (Eds.), The Huasteca; Culture, History, and Interregional Exchange. University of Oklahoma Press.

de Vidas, A. A. (2002). The Culture of Marginality: The Teenek Portrayal of Social Difference. Ethnology, 41(3), 209–224. JSTOR. https://doi.org/10.2307/4153026

Diehl, R. A. (2000). The Precolumbian Cultures of the Gulf Coast. In R. E. W. Adams & M. J. MacLeod (Eds.), The Cambridge History of the Natice Peoples of the Americas: Mesoamerica (Vol. 2). Press Syndicate of the University of Cambridge.

Richter, K. N. (2010). Identity Politics: Huastec Sculpture and the Postclassic Intenarional Style and Symbol Set. University of California Los Angeles.

Richter, K. N. (2015). Postclassic Huastec Sculpture: Constructing International Elite Identity in the Huasteca. In K. A. Faust (Ed.), The Huasteca; Culture, History, and Interregional Exchange. University of Oklahoma Press.

Stresser-Péan, G., & Stresser-Péan, C. (2001). Tamtok, sitio arqueológico huasteco. Volumen I: Tamtok, sitio arqueológico huasteco. Centro de estudios mexicanos y centroamericanos. https://doi.org/10.4000/books.cemca.4322

Taube, K. A. (2015). The Huastec Sun God: Portrayals of Solar Imagery, Sacrifice, and War in the Late Postclassic Huastec Iconography. In K. A. Faust & K. N. Richter (Eds.), The Huasteca; Culture, History, and Interregional Exchange. University of Oklahoma Press.

Wyllie, C. (2015). In Search of Tamazunchale “Place Where the Woman Governs.” In K. A. Faust & K. N. Richter (Eds.), The Huasteca; Culture, History, and Interregional Exchange. University of Oklahoma Press.