Amazonia

The Amazon rainforest has always been a place of mystery and wonder for those outside its borders. When most people think of its inhabitants they picture small tribes hunting and gathering for their meals. Or perhaps you’ve heard stories of lost civilizations hidden deep in the jungle. There is some truth to both these claims, and falsehoods for both as well.

The Amazon is a huge region – and one that doesn’t make it easy to do fieldwork. It is only somewhat recently that the area has reached the archaeological zeitgeist we are seeing in the news today. For a long time research was stunted by archaeologists underestimating ancient people and their ability to shape the environment to their needs. They thought ancient people could not farm because the soil quality was so poor (Roosevelt, 2022). We now know that people learned how to deal with that by creating their own soil – terra preta. This was a combination of waste and charcoal from burning bio materials. It is incredibly rich in nutrients. Since our understanding of this soil has progressed, we are able to see how what are sometimes referred to as “complex societies” developed.

Research here may still be young, but it’s far too much for me to convey in one writeup. What you will find below is an exploration into several large cultural groups that were expanding prior to European arrival. This is the Amazon during the late precontact period, which covers a range of time from about 1000 AD – 1500 AD. I have tried to synthesize these cultures to the best of my abilities, but new research is being released almost monthly. If something interests you here I strongly recommend pursuing further research as I can only outline so much. And to the dismay of some, there will be no discussion of aliens in our coverage of “lost civilizations.”

Introduction to a Pre-Columbian Amazon

It may seem strange, but the ancient Amazon was a much more populated place than it is today. Sprawling villages were established along riverbanks, and roads shot from one to the next in straight lines reminiscent of highways. Trade, colonization, and warfare were commonplace as leaders dealt with one another. At a broader level, there may have been kings who ruled over thousands of people and other minor lords.

With societies at this scale you might ask, where is the evidence? Where are the ruins? You would think that there would be something to show for it akin to the Maya or Aztecs right? Unfortunately, the harsh jungle environment of the rainforest breaks down most biological materials quickly. Another likely reason we don’t see ruins at the scale of those north in Mesoamerica is the lack of stone in the Amazon. Builders were using materials such as wood and palm fronds, which only exacerbate the degradation problem even further. Despite these unfortunate circumstances, we do have some surviving evidence: the most compelling is the landscape itself. Amazonian peoples built tens of thousands of mounds throughout the jungle in conjunction with their village sites. These mounds would act like platforms for buildings, a place for rituals, and served as burial sites. These functions will be explained in more depth below.

When we talk about these archeological sites and cultures it’s important to understand their scope. News articles about research tend to dramatize the findings as “lost cities.” These new discoveries are undoubtedly exciting, however the settlements that we have found (so far) are likely not what you think of when you hear the words ‘lost city.’ They are described by archaeologists studying them as examples of low density urbanism. This means we are finding settlements which are spread out and have elements of a growing population – they’re intensifying their land use with more agriculture, the political climate seems to have been growing increasingly more complex and competitive, and warfare was becoming more commonplace. Perhaps with a few hundred more years without European intervention, we truly could have seen population densities rival that of Mesoamerica.

Civilizations of the Amazon

Marajoara and the Mound Builders (800 – 1400 AD)

Marajoara Island is a large landmass at the mouth of the Amazon River, on the eastern side of Brazil. To put the size into perspective, it’s on par with the state of Connecticut. In the field of Brazilian archaeology, the island has been one of the longest studied regions since its introduction to the European world in the 1870s.

Found all throughout the island are mound complexes (human made earthen structures) that contain artifacts and burials. There are many reasons we can speculate about why mounds were built. One reason that does not require any speculation becomes clear when we look at the landscape. Marajoara flips between a state of flooding in the rainy season, and near drought conditions in the dry season. During the wet season, as rain falls on the impenetrable clayey soil, the rivers swell beyond their shorelines and envelop the entire island. You can’t go anywhere without soaking yourself – anywhere except these mounds. The only areas which stay above the water level year-round are these man-made structures (Young-Sánchez & Schaan, 2011). Therefore, if you want to live on the island, it is almost necessary that you create infrastructure to stay dry which is what these people did.

So far, the mound complexes appear to be individual entities (Roosevelt, 2022). You could think of these similarly to something like Greek city states. They all shared the same general culture, but they probably governed themselves individually. We have not found evidence for any administrative centers, but each complex does have elite mounds. The role of elites in Marajoara society will be explained below.

Life on the mounds was a communal one. Some could hold up to twenty longhouses on top, and within these longhouses there would be multiple different families. Unfortunately, the wood that these buildings were made with quickly decomposes in the jungle, therefore we have to use postholes and remnants of the hardened clay floors to speculate what they looked like (Schaan, 2011). A series of hearths lined the centers of these houses, with each hearth likely corresponding to a smaller family group.

Elite mounds are signified by their proximity to food sources in villages, taller height, and their more exotic artifact collections. These mounds would be found near the village ponds. Fish and turtle ponds would be constructed as rivers receded from the land during dry months. By trapping fish in small ponds, hunting would not be necessary, and protein would be within easy reach. In village sites which utilize these fisheries, we see the largest mounds (with elite status artifacts) built in close proximity – often overlooking the ponds (Schaan, 2011). It is hypothesized that this was more than coincidence. Placing yourself near the food source is a direct marker of status and reinforces your right to rule, seeing as you can provide for your people.

If there is evidence of an elite group, then the society must also be a ranked one with different status groups. Many archaeologists share a similar view that political status in pre-Columbian Amazonian societies was linked to your ancestor’s power. Today, ancestor veneration is a popular tradition amongst indigenous tribes in the region; it seems to have been in the past as well. One of the major mound types in Marajoara and elsewhere is a cemetery style. Individuals interred here were buried in decorative urns that ranged in how elaborate they were. This would be according to the individual’s status in society. Images on the urns were often anthropomorphic and also zoomorphic, related to Amazonian myths, depicting snake and owl motifs.

It is likely that Marajoara society was a matrilineal one. This means that land rights – and maybe more importantly, water rights – were passed down through the mother’s side. The vast majority of ceramic artifacts are stylized depictions of women, and if a typically male symbol such as a phallic figurine is created, there are still female elements on it (like a vagina or a tanga, which is a female pubic covering) this blending of genders could be a showing of appreciation for the role women have in lineage creation (Schaan, 2011).

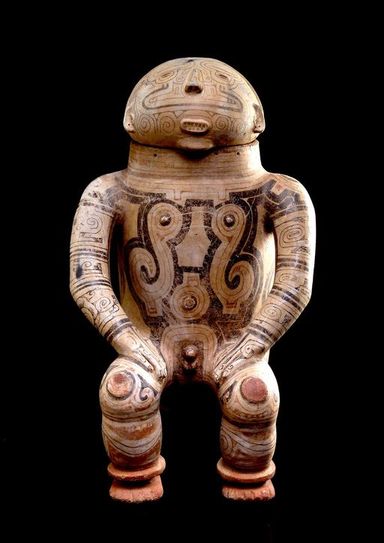

An interesting comparison is that of Marajoara and Santarem ceramics. The Santarem are another cultural group which we will talk about below. Santarem ceramics have a much more balanced representation of male and female depictions. Denise Schaan, a prominent Amazonian archaeologist, believed that this could be indicative of a more male-dominated society as men led rituals and activities in society. She also takes note of the more realistic depictions in Santarem figurines and ceramics. They could be depictions of actual individuals, rather than abstractions of ideas. Marajo elite ceramics comparatively show little realism in their depictions. It seems like they may be a celebration of caste and that individual within it, rather than depicting the person as they were. This may seem like a small distinction, as both groups are still celebrating elite figures – but it gives us a deeper understanding of their worldviews. Santarem people may have been moving towards a celebration of their political leaders, whereas Marajoara people were representing the political power of the elite caste. Regardless of these shifting ideals, both groups still shared a celebration of prestige through their ceramics.

Far left: One style of a Marajoara burial urn depicting a male.

(Museu Barbier-Mueller d’Art Precolumbi)

Left: Another style of funerary urn.

(H. Law Collection)

Within these urns we have found grave goods that range from stone axes and necklaces (stone is rare and sought after resource in the Amazon) to tangas.

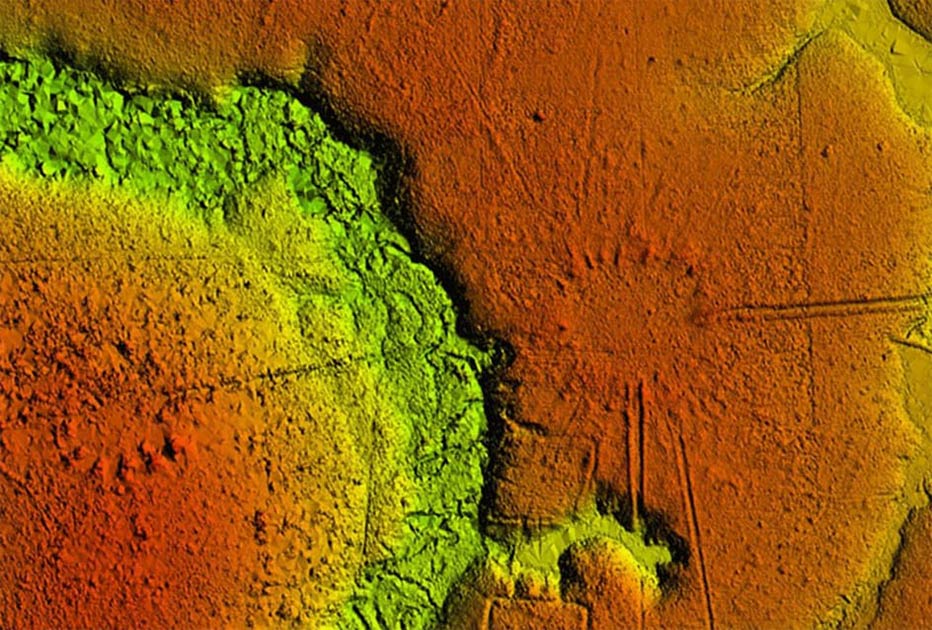

Above: The remains of a human-made mound on Marajoara.

(Elilope, Wikipedia.)

The Xinguano’s (1250 – 1650 AD)

A useful tool to understand the lifestyles in ancient settlements is through observing modern indigenous groups. Pax Xinguana is a term coined by Michael Heckenberger, an ethnohistorian and archaeologist who’s worked with Xinguano tribes in the southern Amazon. The term is in reference to their ancestral sphere of influence and the relationship between these villages. They would have been inhabited from around 900 AD to 1500 AD by the ancestors of the Xinguano people. Heckenberger lived with these tribes in order to understand their ways of life better and how their cultural practices could be transcribed into prehistory. This ethnographic approach can be helpful when there is such limited archaeological evidence to tell us about past lifeways.

Something that Heckenberger points out in his research is that modern groups don’t always recall their links with these ancient villages. When he brought village elders to the sites he was doing research, they had no recollection of their people living there. After some discussion they did recall a time where there was more violence between tribes and their people had to build walls – a feature of the archaeological site he was showing. Despite the tribes not always having recollection of where their ancestors settled, or remembering the nuances in their lifeways, he theorizes that modern groups have historical practices embodied in their culture. Manioc production, for example, has remained unchanged since the crop was first discovered (as indicated by the tools in the archaeological record). It can be assumed that many of the other adaptations and traditions of modern groups have been in use since times of prehistory.

Let’s dive deeper into the term Pax Xinguana by looking at the layout of one of these ancient settlements. As you can see, there are circular rings around the nucleus of the village. These rings would have been moats, and usually had tall wooden palisades lining them as well. We see an intensification of defensive architecture all throughout the Amazon around this time. Understanding who these conflicts were between is another opportunity to use a collaborative approach between archaeology and modern ethnographies.

These archaeological settlements are believed to have been settled by the Xingu’s ancestors – members of the Arawak language group. It is well documented that Arawak people have a strong disposition towards nonviolence. They associate the killing of other humans as spiritually polluting, and even the act of hunting or handling red meat as repulsive. This outlook has influenced their primarily fishing and manioc based diet. The Guarani – another Amazonian group – has a recorded history of an aggressive and violent nature. The Guarani are mobile hunter gatherers who have a recorded history of raids on Arawak villages. Men in Guarani villages see themselves as hunters and abhor the idea of fishing or growing crops. The stereotype of cannibal headhunters was influenced by the practice of these groups. Raids by Guarani groups were not only for the acquisition of resources – but often to destroy the entire rival community as well. These raids were recorded by Europeans, but they undoubtedly were happening before contact as well (Heckenberger, 2005).

It makes sense that the creation of defensive architecture in Xinguano villages came about as a necessity to defend from antagonistic outsiders. The walls were not created to defend themselves from other walled villages, but rather to defend from mobile war parties. Roads linking Xinguano settlements is another indicator that relationships were amicable.

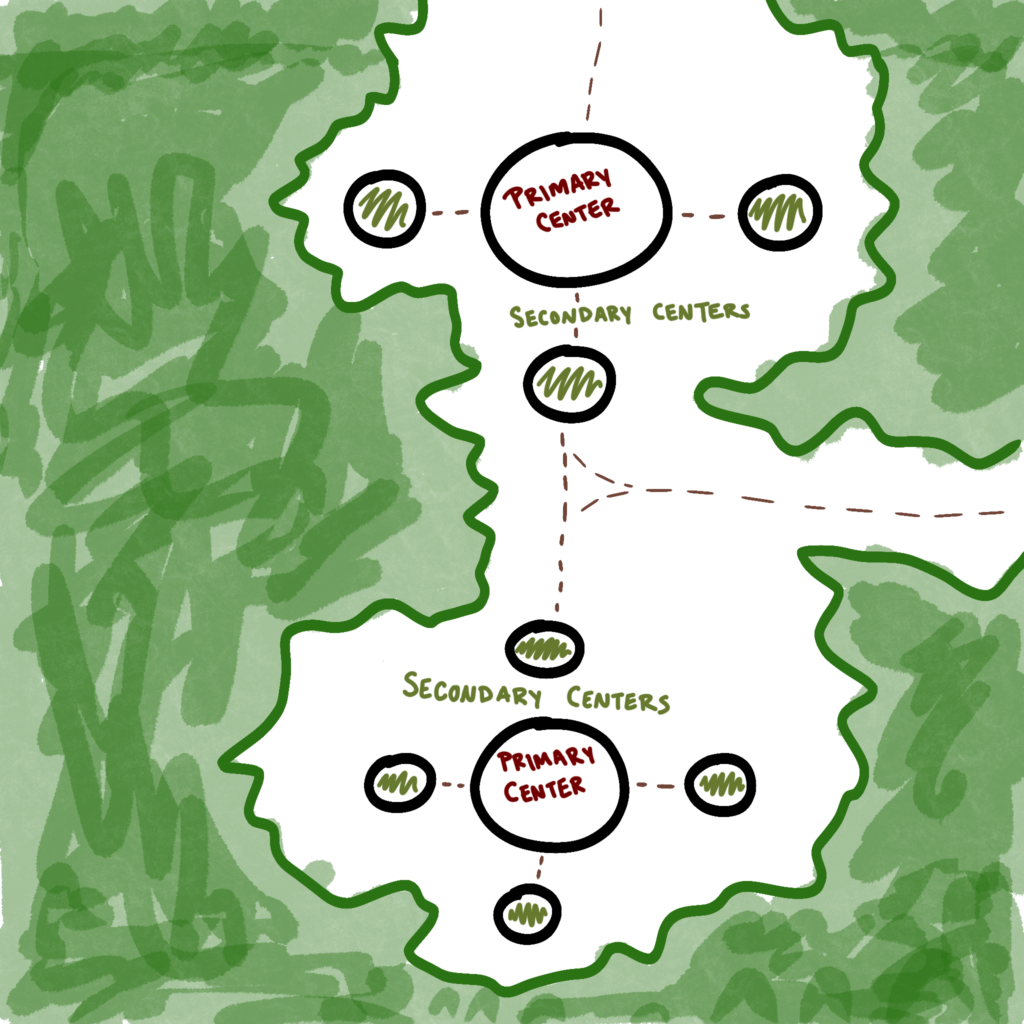

These settlements were organized in clusters. Some have grand plazas but no residential infrastructure. Others were primarily residential with a small plaza in the middle. Larger sites that lack housing tend to be found at the center geographically, surrounded by other satellite villages. This could mean that they were administrative centers, or perhaps ritual spaces – maybe both. There is a suspected hierarchy at play here as well. Like Marjoara, the status of your ancestors would likely rank your village. The more grand they were, the higher ranking your village would be in the cluster. The larger central settlements may have been reserved for the most powerful of rulers. Ritual acts and performances would have been a large factor in determining where you stood as a leader (Heckenberger, 2005).

All of this evidence hints at a greater organization of villages than we once thought. Unfortunately, we do not have the chance to view inter-village relationships as they once were. Modern groups are not organized the same. Each village acts as its own polity and these clusters are now non-existent.

An illustrated rendition of two Xinguano village clusters.

People typically lived in the secondary centers and traveled to the primary center for ritual activities. Roads connected the clusters over long distances.

Greenstone and an Economy of Rocks

Stone is a rare resource in the Amazon. For that reason, when it is found its placement is often due to humans. Unlike organic materials, it does not decay in the jungle environment either, which makes it of particular importance to archaeologists.

Greenstone is a group of stone types, but often referred to as jade in areas outside the Amazon. These rocks are intricately carved into figurines which depict animals and humans, and most commonly frogs. They are well known to be symbols of status north in Central America. Ethnographic accounts in the Amazon corroborate that this is the case in South America as well – perhaps even moreso for its rarity and difficult supply chain. Costa Rica is thought to be the southernmost place that these rocks were sourced, so their movement into Amazonian chiefdoms would have been slow and through intermediate traders. The Santarem culture seems to have facilitated this trade, with workshops having been found at various archaeological sites along nearby rivers within their territorial boundary (Schaan, 2011).

These trinkets would have been highly sought after and used as a valuable trading tool. They likely facilitated good relations between groups and would have been an admirable offering. Brides may have been exchanged with these stones as a marriage gift to the family. To have an object like this, was to have something of great rarity and prestige.

The frog motif was a popular one, and aptly chosen as greenstone was thought to have been crafted out of mud underwater, and when it was exposed to air it solidified into the figurines we know today. Frogs symbolize aquatic beings, so their depictions in greenstone was appropriate. These figurines would often have holes drilled through them so they could be worn on necklaces by elite women in villages, as recorded historically (Roosevelt, 1999; Schaan, 2011).

An interesting style which is much rarer to find are anthropomorphic depictions. These greenstone artifacts commonly show a human figure with an animal on their back or over their head. Another common feature is two stacked holes on the back of the object. Researchers have two different theories on the nature of these greenstone artifacts. They may have been idols due to ethnohistoric accounts recalling that Amazonians would carry stones as good luck charms whether they were fishing or going to war. The holes could have been for attaching the object onto the front of a boat to bring good luck fishing. The other idea for their use is as a transitory tool when going into a shamanic trance. Rods would be inserted into the holes as a way to take snuff hallucinogens and the animals would have been a symbolization of the shaman’s transformation. To make matters more complex, is that the style depicted looks nothing like other Amazonian depictions of humans, and more akin to a Southern Central American art style, such as that of Nicaragua (Schaan, 2011). More research is needed before a conclusion can be made as to whether or not this is a foreign import or crafted locally like other greenstone objects.

Image credits:

The frogs: Denise Maria Cavalcante Gomes from Museu Nacional-UFRJ and private collection.

Axes: Alexandre Bernand from Sothebys Paris and the British Museum

Here is a fantastic article associated with the axes

Santarem (1000 – 1600 AD)

The last culture to be discussed in this article is that of the Santarem. This group can be found upriver from Marajo island, at the junction between the Amazon river, and the Tapajos river. While we can see some similarities between the Marajoara and Santarem, they are also distinct from one another and should be treated as such.

Before we begin, I want to mention that the Santarem are the most looted and fragmentary archaeological culture we will discuss. If you were to google “Santarem” the first result would be the modern Brazilian city which has the same name. So, more appropriately, this archaeological culture bears the name of the city that was built on top of it. As the city has grown in size and become a popular tourist destination, sites have been destroyed to make way for development (Roosevelt, 2022). Despite these unfortunate circumstances, the Santarem culture did exist into early colonial times, and we have some accounts of how their culture operated. These accounts were recorded by colonizers, however, and were taken during the terminal stage of the culture so they may not be accurate for the entirety of Santarem’s existence. It should also be mentioned that the Santarem sphere of influence was larger than where the modern city stands, but the city was definitely an important regional center.

Photo credits: Museu Nacionale Brasil

Evidence shows us that Santarem cities expanded for many kilometers along riverbanks. The smaller villages had between 20 to 30 longhouses and a hierarchical system of chiefs. These longhouses sat on long mounds. European accounts wrote that they encountered rulers who claimed to be descended from gods. Under these god kings there would be a group of lesser elites, and then finally residential leaders. Women were able to rule (at latest to some extent) as the Europeans recorded an elite woman as a community leader. There was also a significant female religious leader who was noted by the Europeans, however they never saw her and archaeologists hypothesize that this may have been a deified ancestor (Roosevelt, 1999).

Like the other cultures we’ve discussed, the Santarem had a complex system of ancestor worship. Many ancestors were cremated and held in urns. There are also accounts of ancestors’ bone dust being consumed in drinks after they had been cremated. If it was a particularly important ancestor – perhaps one of these godly rulers – they would be mummified and stored in special houses to later be brought out for ceremonies (Roosevelt, 1999).

The Santarem grew manioc and fished for their subsistence. Interestingly, they also grew and consumed maize in large amounts which is particularly unique among Amazonian peoples. Some Santarem communities even preferred maize over manioc as their staple crop (Roosevelt, 1999). It is unknown why the Santarem had more of an inclination towards maize than other Amazonian cultures, but we do see it popularized throughout the culture and consumed by all classes.

The populations in Santarem settlements appear to have been quite large and peaked in the late precontact period. The archaeological record indicates that when Europeans met these groups they had already been shrinking for some time. Regardless, they were still formidable enough to fight back against early colonizers with large war parties. War canoes reportedly held up to 60 individuals, who were conscripted from mandatory village levies. Slaves were also observed by European colonizers, meaning that there must have been a preexisting system of warfare or raids.

During the fourteenth century we begin to see smaller sites establish themselves on hilltops within hiking distance to the Tapajos river. These sites would have a clear viewshed in all directions, and an ability to conceal themselves better than the larger sites found along riverbanks. Some researchers hypothesize that this geographic relocation was in response to growing populations in settlements around the Santarem area. Higher populations could have led to more conflict between communities. These hilltop communities would be safe as they occupied the hinterlands – a less desirable region (Gomes et al., 2023).

Conclusion

I hope you have enjoyed this brief exploration into the ancient Amazon. Before you go, I want to iterate that these groups are not gone. While their population numbers took a heavy blow throughout the last couple centuries, their descendants live on. The ancient cities were not made by a mysterious people disappearing into thin air – they abandoned those cities to escape the European world which was rapidly invading their homeland. Either that, or they assimilated to it and are now Brazilian citizens. The reasons that these cities may seem strange and mysterious now is because the people have had to live so far removed from them that even to village elders they are being forgotten about in collective memory. If you find this topic interesting, I urge you to learn more and educate others.

References Cited

Gillman, M., & Erenler, H. (2009). The Genetic Diversity and Cultural Importance of Cassava and its Contribution to Tropical Forest Sustainability. Journal of Integrative Environmental Sciences, 6(3), 189–200. https://doi.org/10.1080/19438150903090509

Gomes, D. M. C., Costa, A. F., Munita, C. S., & Da Cunha, J. P. L. (2023). Archaeological Evidence of the Development of a Regional Society in Santarém (AD 1000–1600), Lower Amazon: A Path to Understanding Social Complexity. Journal of World Prehistory, 36(2–4), 147–189. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10963-023-09177-3

Heckenberger, M. (2005). The Ecology of Power: Culture, Place, and Personhood in the Southern Amazon, A.D. 1000-2000. Routledge.

Roosevelt, A. (2022). The Sequence of Amazon Prehistory: A Methodology for Ethical Science. Tessituras: Revista de Antropologia e Arqueologia, 10, 11–44. https://doi.org/10.15210/TES.V10I1.22886

Roosevelt, A. C. (1999). The Development of Prehistoric Complex Societies: Amazonia, A Tropical Forest. Archaeological Papers of the American Anthropological Association, 9(1), 13–33. https://doi.org/10.1525/ap3a.1999.9.1.13

Schaan, D. P. (2011). Sacred Geographies of Ancient Amazonia: Historical Ecology of Social Complexity. Left Coast Press, Inc.

Young-Sánchez, M., & Schaan, D. P. (2011). Marajó: Ancient Ceramics From the Mouth of the Amazon. Mayer Center for Pre-Columbian & Spanish Colonial Art at the Denver Art Museum ; Distributed to the trade by the University of Oklahoma Press.