Beneath Oregon’s landscape lies the traces of its ancient past. A time when the landscape was covered with ice and beasts long forgotten. While the world has changed greatly over the centuries, there are still hints at what had come before. As archaeologists, it’s our job to make sense of these changes and figure out the story of how we got here. This article concerns itself with one of the earliest cornerstones in North American history – the colonization of Oregon. It is a hot topic in archaeology today as the earliest human occupation of the Americas steadily edges further back into the past with each new discovery. This has led to debate surrounding the validity of dating in these early sites. I do not wish to enter that debate myself, as there are already many online sources outlining the arguments. However, I will say that the antiquity of these sites seems valid to me, and I will treat them as such in this article. Instead of a debate, I think it would be much more entertaining to talk about what this new landscape was like for the first people. I’d like to talk about the food they ate, the things they saw, and how they lived. Let’s delve into the Oregon of the ice age.

The Coastline

An integral part of this story is the coastline. What you may have heard in school is that people came to the Americas across the Bering Strait. While that is likely the case later in history, date ranges for the earliest American sites correspond to a time when this passageway would have been still covered in ice (Scott et. al, 2021). Therefore, we can assume that some people were coming to the Americas by boat. The argument against this coastal migration theory is because there is a lack of sites on the coastline – however we also must take into consideration that the world’s sea levels were lower. This would have resulted in a coast that is around 10 to 40 miles further out at sea than where it is today. As ice has melted, the evidence of early sites likely has been drowned.

Still, with speculation and reasoning we can paint a realistic picture of what the coast may have been like to those who lived there. Even in the harsh and cold time of the ice age, living at the frigid shores of a new continent could have been considered a refuge. It would have been free of ice and had obtainable food resources. Groups moving along the coastline would have access to fish, shellfish, and marine mammals like otters. It’s been proposed that kelp forests thrived under glacial conditions – and they would have held more plentiful aquatic resources, however there needs to be more research done before it can be said with certainty (Davis, 2020).

Genetic evidence shows us that Native Americans share DNA with Siberians (Scott et. al, 2021). The Siberians who decided to leave their homeland would have traveled by island hopping from the Kamchatka Peninsula (in the easternmost part of Siberia) to the Aleutian Islands, and down the coast of Alaska and the Pacific Coast of the Americas. The northern ocean is rough water, so these groups would have had to cling to island chains if they wanted safe passage. It is likely that small groups colonized this new landscape, moving from one inlet to the next in a hunting-fishing-gathering lifestyle. Perhaps they could see the ice sheets inland which dominated the entirety of the continent north of (and covering) the modern state of Washington. It’s interesting to think about how they felt, as they skirted along the border of a new world sharing knowledge with one another. These groups would have traded when they had the chance, mingled, married, and ate together. While the coastline was a new frontier, it was also a growing highway.

The Channel Islands

The Channel Islands off the coast of Southern California show us how extensive this coastal colonization was. These islands have never been connected to the mainland, even with the lower sea levels of the ice age, meaning that people have always needed to use boats to get there. Stemmed points that date to around 12,000 years ago were found on the islands (Erlandson et. al, 2011). This indicates that the island’s first inhabitants were people who shared the same cultural tradition as those in Oregon and elsewhere along the Pacific coastline. These settlers were the ancestors of the Chumash people who resided on the islands until the time of European contact. Shipbuilding was, and still is, a vital aspect of the Chumash way of life. They construct a robust canoe known as a tomol. Traditionally these boats were made from redwood logs that washed up onto the shoreline, and after construction they could hold up to 10 people. With the little evidence we have (as wood doesn’t last long in the archaeological record) it is impossible to say how shipbuilding has changed in the last 12,000 years. Perhaps the earliest settlers’ boats resembled these Tomols – or maybe they looked completely different. Regardless, it is interesting to see such a long continually inhabited area, with a maritime culture that has survived throughout history since the first settlers. If you are interested in learning more about Tomols, here is a very interesting video about the modern Chumash keeping their cultural traditions alive in their community.

The Great Basin

Eventually, some groups would move inland – maybe the coastline became too crowded, or perhaps they were in search of more fruitful land. These explorers would stick to their boats for a time, following rivers from the coast. Deeper into the continent they would find animals and plants unfamiliar to them or their ancestors from Siberia. In this strange land there were sloths measuring 20 feet long, with claws over half a foot in length. Looking over the side of their rafts, these humans may have spotted giant beavers swimming alongside them. Setting up their campsite in the evening, the humans may have felt a rumble within the ground – this was no earthquake, however. Approaching nearby would be a herd of mammoths, the largest animal these settlers had ever seen. The children would stare in awe and confusion. Unlike the stories their grandparents told them from their old home, these mammoths didn’t have any fur at all. These were known as Columbian Mammoths. It’s likely that the herd was led by the oldest female, known as the matriarch. She led them on their migrations in search of places that had the most abundant food and water. After a long look, the children’s mother would shoo them back towards the group. She would remind them that this land had lions and sabertoothed cats with fangs the size of the child’s arms – and that’s not even mentioning the bears that lurked in the caves.

This is just a snippet of what life may have been like on the interior of the continent, as small groups trickled into the area we now call the Great Basin. It was a much cooler and wetter environment than it is now. Where there are deserts today, there were large shallow lakes. The land would have been covered in grassy fields. Many archaeological sites we find from this period are in inhospitable and barren places that would make you wonder why anyone would live there. In reality, the people who settled there did so on beaches and enjoyed a much different life than the environment could sustain today.

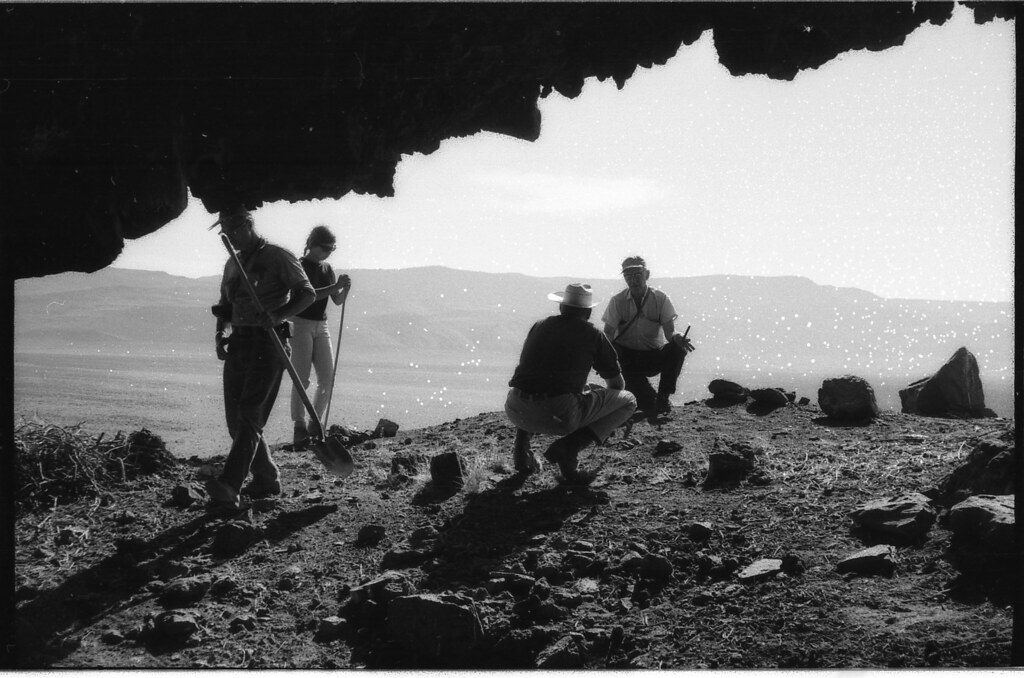

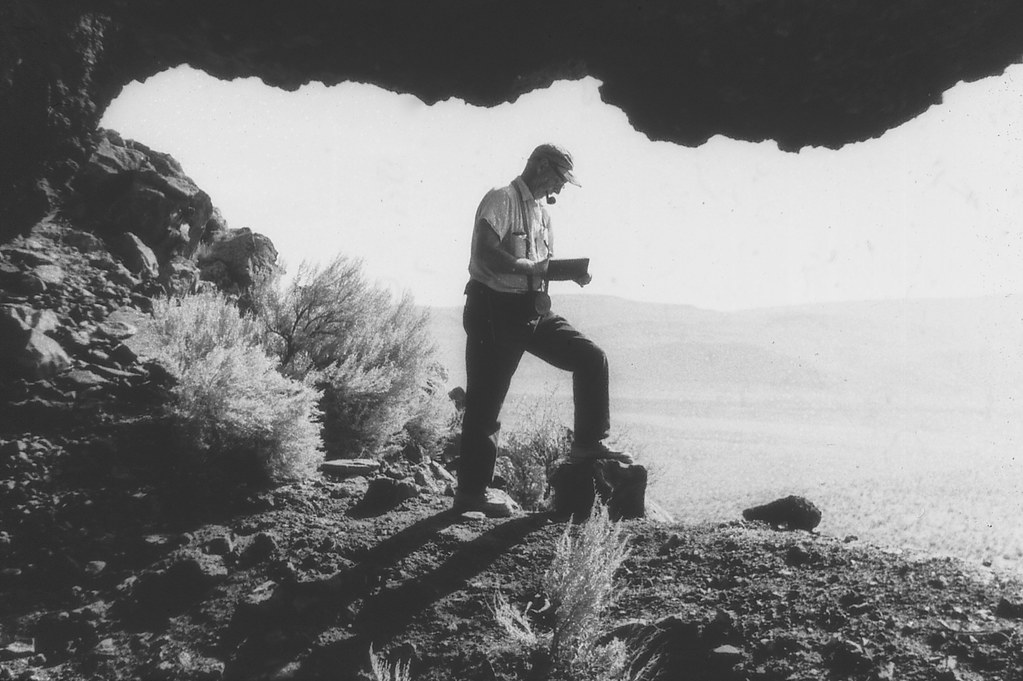

Instead of talking in abstracts, let’s look at one of these archaeological sites: the Paisley Caves. In Oregon archaeology, the earliest cultural period is called the Paisley Period, named after this rock shelter. The caves are found in south central Oregon, in the rain shadow of the Cascade mountains. If you are unfamiliar with the geography of Oregon, this is actually a desert today. In the Pleistocene, right outside the caves these humans called home, there would have been the shorelines of a pluvial lake – meaning that the water had accumulated there through rainfall. As you may expect from what we’ve already discussed, this lake is no longer there.

The Paisley Caves have held many artifacts and faunal remains for thousands of years. They contained stemmed points, cordage, and a bear bone with grooves carved into it for unknown purposes. Fortunately for us, one of these caves was also a bathroom. Fossilized poop – known as coprolites – is a dateable material, and it’s extremely helpful in reconstructing past diets. The evidence indicates that humans occupied the cave around 14,500 years ago, making it one of the oldest sites in the Americas (Aikens, 2011; Jenkins et. al, 2012). We also learned that the humans living there were eating a diverse omnivorous diet. We’ve found evidence of plants, bison, camels, horse, sheep, pronghorn, rodents, canids, and bugs. The stereotypical idea of a Paleo-Indian diet is one of carnivorous hunters exclusively surviving off mammoths and bison. That wasn’t the case here. The people were eating what they could and utilizing all the resources the environment provided them. I do want to note that Clovis are typified as these big game hunters, and I don’t want to perpetuate that as wholly true. Humans are humans, and while they may have preferred certain foods, they weren’t passing up the chance to eat.

What Happened After?

This brings us to the end of our discussion of Oregon in the Ice Age. As time progressed, the lonely landscape would begin to fill with more families and tribes. As the ice sheets receded and a pass opened through the Bering Strait, many more people would colonize the continent from the north to the south. Slowly, those who settled in the Great Basin during the last ice age would see their ancestral lands becoming more and more dry. Their only respite from this aridity would come in the form of a volcanic eruption from Mt. Mazama 7,700 years ago. The eruption would have been a catastrophic geological event, leading to the creation of Crater Lake, as the volcano collapsed inward on itself. This event would be remembered in indigenous oral histories for thousands of years. After the eruption, the cooler climates returned but only for a few centuries, and afterwards the landscape in the Great Basin turned into the desert landscape we know today (Aikens, 2011). Those who decided to stay adapted by becoming highly mobile people who continued to utilize whatever food resources they could find. On the coastline, groups still moved between inlets for much of history until around 4,000 years ago, when they began to organize themselves into sedentary and highly structured societies (Aikens, 2011). Around this time, their settlements became permanent, and the coastline became a more densely occupied area.

The Western Stemmed Tradition

Unlike the Clovis points you may be familiar with, the west coast of America had a vastly different projectile point tradition during this time. It is called the Western Stemmed Tradition and is a group of points that all have a stemmed base, instead of the typical Clovis flute. As you can see, there’s tons of variation in these points, and we don’t have answers for that. Possibilities that have been proposed are anything from resharpening events, to being created by different ethno-linguistic groups, or different uses that aren’t understood (Rosencrance, 2019). Despite that, these points were typically created from flakes and share a few similarities. They are narrow, with pronounced shoulders and a thick base that gets narrower at the bottom (Erlandson et. al, 2011). As I mentioned earlier, the Channel Islands have sites with these points, and so does Oregon, Washington, Idaho, Nevada, and California. It seems to have been a purely western phenomenon. Researchers have noted that these points have an uncanny resemblance to others being created at the same time in Japan, known as the incipient-Jomon culture. This only adds to the mystery, however, as DNA evidence shows that the Jomon were not the source population for the Americas (Scott et. al, 2021). Despite the lack of DNA overlap, I still wonder how much communication was happening between Japan and the Siberian colonizing group, as the tools do look similar, and they both were maritime cultures.

Now let’s return to the Western Stemmed Tradition. The sites we are finding predate Clovis, are contemporary with, and postdate Clovis too – so this was a longstanding tradition. If you are wondering if Clovis people interacted with those of the Western Stemmed Tradition, they did. Archaeological evidence shows that sometime during the Paisley Period, Clovis people entered the region. We can see this interaction at the Dietz site in Central Oregon. The site contains stemmed points and Clovis, both during the same occupation, but in different concentrated areas (Aikens, 2011). We don’t have a strong idea about how these interactions played out, but we can make some guesses. Clovis people are typically associated with hunting large megafauna (like mammoths and bison), and while that is a narrow way to view them, it seems to have been a defining and important aspect of their diet and culture. The sites we are finding with WST points are showing us that they had a broader diet than what is thought of with Clovis. Perhaps we could view Dietz as a meeting ground of cultures. Clovis, coming from the east may have brought bison and mammoth meat, and the WST peoples brought camel and horse. Maybe the Clovis knappers tried to show the westerners how to make their distinctive tools – but while the Clovis points are good for taking down large game, the western people had no need for such a point. Some western people may have still adopted the knapping style because of its aesthetic beauty; others may have not bothered. Right now, there are more questions than answers, as is the way with archaeology.

References Cited

Aikens, C. M., Connolly, T. J., & Jenkins, D. L. (2011). Oregon Archaeology. Oregon State University Press.

Davis, L. G., & Madsen, D. B. (2020). The Coastal Migration Theory: Formulation and Testable Hypotheses. Quaternary Science Reviews, 249, 106605. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2020.106605

Erlandson, J. M., Rick, T. C., Braje, T. J., Casperson, M., Culleton, B., Fulfrost, B., Garcia, T., Guthrie, D. A., Jew, N., Kennett, D. J., Moss, M. L., Reeder, L., Skinner, C., Watts, J., & Willis, L. (2011). Paleoindian Seafaring, Maritime Technologies, and Coastal Foraging on California’s Channel Islands. Science, 331(6021), 1181–1185. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1201477

Jenkins, D. L., Davis, L. G., Stafford, T. W., Campos, P. F., Hockett, B., Jones, G. T., Cummings, L. S., Yost, C., Connolly, T. J., Yohe, R. M., Gibbons, S. C., Raghavan, M., Rasmussen, M., Paijmans, J. L. A., Hofreiter, M., Kemp, B. M., Barta, J. L., Monroe, C., Gilbert, M. T. P., & Willerslev, E. (2012). Clovis Age Western Stemmed Projectile Points and Human Coprolites at the Paisley Caves. Science, 337(6091), 223–228. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1218443

Rosencrance, R. (2019). Assessing the Chronological Variation within Western Stemmed Tradition Projectile Points.

Scott, G. R., O’Rourke, D. H., Raff, J. A., Tackney, J. C., Hlusko, L. J., Elias, S. A., Bourgeon, L., Potapova, O., Pavlova, E., Pitulko, V., & Hoffecker, J. F. (2021). Peopling the Americas: Not “Out of Japan.” PaleoAmerica, 7(4), 309–332. https://doi.org/10.1080/20555563.2021.1940440